It’s hard to know where to begin with this family. It is many things: awesome, intimidating, expansive, difficult to categorize. I first became aware of it from the book Island Life by Sherwin Carlquist, a fascinating collection of essays on the unique patterns of evolution occurring on islands and other remote habitats. Many species of Campanulaceae evolved in such habitats.

The 2,400 species of this family exist on all continents except Antarctica. Their habitats are diverse: from dry deserts, the Arctic, sea cliffs, and alpine environments to rainforests, lakes, and tropical forests. They take many forms, from slender-stemmed creepers to ground-hugging rosettes to palm-tree doppelgangers.

Diverse Plant Forms and Unique, Showy Flowers

Plants in this family take many forms but share some common characteristics like hairy plant parts and tall, spiky reproductive structures. The frequently tubular, bell-shaped flowers give the family its common name—bellflowers—and entice bees and birds, especially those with long beaks like hummingbirds.

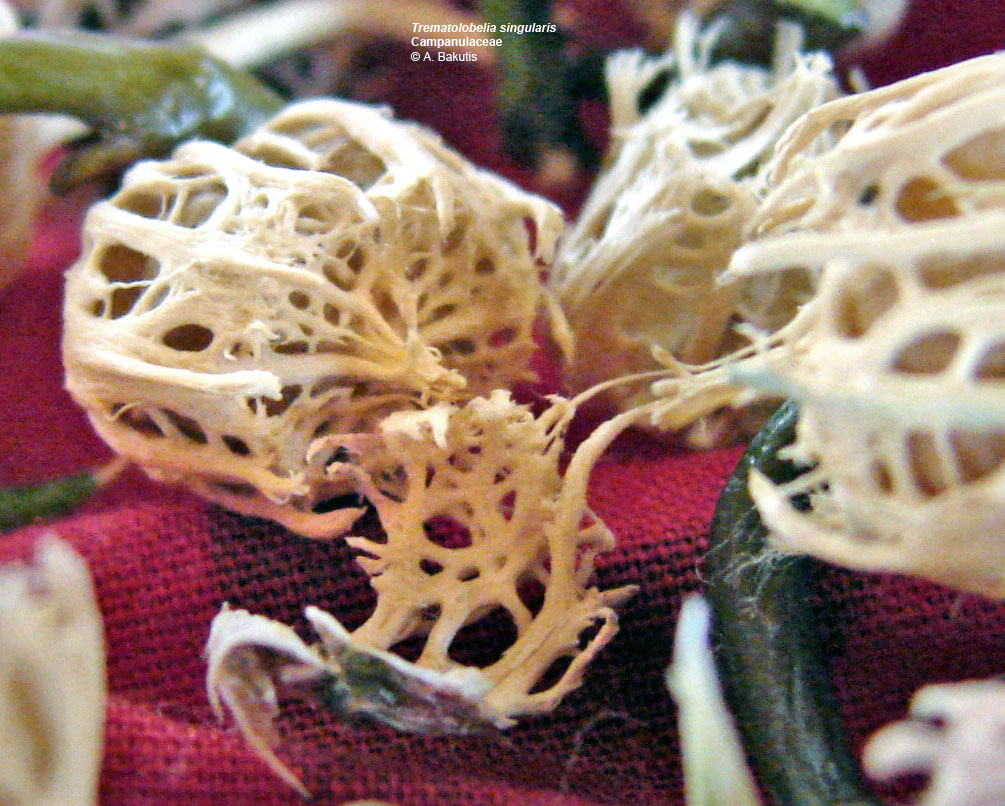

The seed capsules can also exhibit a unique shape that seems more akin to art than nature. The mature fruit capsules of harebells and campanulas break open via pores on their sides. Rather than drying and splitting apart, the outer wall of Trematolobelia fruit disintegrates into a perforated, seemingly manmade structure with holes through which the seeds escape.

The lobelias are particularly wide ranging. Each plant of L. deckenii, which grows in moist valley bottoms of mountains of East Africa, can have multiple rosettes which are connected underground. These grow for several decades before producing a single large inflorescence with thousands of seeds. The individual mature rosette dies; the connected others continue on.

Another interesting feature of this plants is that reservoirs of water held in the rosettes freeze overnight and prevent the central leaf from freezing overnight.

On a smaller scale, the water lobelia (L. dortmanna – native to WI) grows in the form of basal rosettes in aquatic environments with flower stalks that reach above the water; rather than using stomata to get CO2, which they don’t have, the roots have the rare ability to obtain CO2.

Others grow in ephemeral sources of water. Water howellia (H. aquatilis) is a wetland plant of Pacific Northwest commonly found in glacial potholes, ephemeral (vernal) pools, and other areas that flood periodically. Submerged, cleistogamous flowers self-pollinate while closed; seeds are deposited in the water and must wait to sprout when the water evaporates.

Rare Island Isolates and Evolutionary Oddities

Some Campanulaceae species are found only on specific islands, where they have evolved unique forms of existence that diverge drastically from their nearest mainland relatives.

An entire article alone could be written about the 125 or species of Hawai’ian lobelioids, the flowers of which are particularly beautiful. It is thought that they all derived from a single species arriving in the Hawai’ian islands around 13 million years ago. The cyaneas (“hāhā” in Hawai’ian) are the largest most diverse of these plants.

Many are endangered or located in such inaccessible spots that it is difficult for scientists to reach them to establish their status. Some haven’t been seen in some time, as in the case of Cyanea dolichopoda, which was last observed in 1992 when only four plants were found growing in the extremely remote Blue Hole valley on Kaua’i. The Limahuli Valley cyanea (C. kuhihewa) was thought to be extinct after Hurricane Iniki but was rediscovered in 2017.

Brighamia species are quite unlike the other Hawai’ian lobelioids, looking more like a palm tree. Cabbage on a stick (B. insignis) is critically endangered and possibly extinct in the wild. It was last recorded in its native habitats on Kaua’i and Ni’ihau in 2014. Its thick succulent stem tapers toward the top where it ends in a spray of cabbage-like leaves. Artificial pollination by humans allows them to continue surviving in botanical reserves and nurseries.

Crevice and Cliff Dwellers: Rock Garden Stars

As Island Life demonstrates, islands aren’t the only “islands”—if we expand our definition a bit, an island could be anything that is isolated, separated, or sharply defined in boundary. Remote alpine habitats can be considered a type of “island.”

Another group of plants in the Campanulaceae family prefer the cooler habitats of remote alpine regions: From the Austrian Alps, to rocky outcrops in Turkey and the middle east, to mountains in China and Central Asia, and to misty cliffs in Africa.

Some of these alpine-loving species are classified as cushion plants, like the Herzegovinian bellflower (C. Hercegovina), which penetrates deep into limestone cliff cracks while the fragile plant head hugs the surface.

Pukeweed: Medicine or Maleficent?

Like many other plant families of this size, Campanulaceae has its own variety of internationally divergent traditional medicinal uses. “Pukeweed” is an apt moniker to sum these uses up.

Many Lobelia species are considered poisonous due to the presence of the toxic lobeline, which is similar to nicotine. Despite this, indigenous peoples used it as a tobacco substitute and purgative to induce sweating, vomiting, or purging. Indian tobacco or pukeweed (L. inflata) has a long history of use as a medicinal purgative and ceremonial plant by Native Americans for a range of conditions mainly respiratory in nature. Devil’s tobacco (Lobelia tupa), native to Chile, has been used to treat smoking cessation because of the lobeline.

Puke-inducing or not, many species are used in traditional Chinese medicine, such as ladybells (Adenophora speces) and Chinese lobelia (L. chinensis), the latter of which is one of the 50 fundamental herbs of traditional Chinese medicine, used to help smoking cessation.

The Modest Vegetables

We can end on a more benign note with the humble vegetables of this family. The most well-known edible Campanulaceae species is rampion (C. rapunculus), which was once widely grown in European kitchen gardens for its spinach-like leaves and radish-like roots. The name of the Rapunzel tale purportedly comes from this plant. The roots are boiled like parsnips and eaten with sauce. Young roots are sometimes eaten raw with vinegar and pepper.

“When Rapunzel’s mother was pregnant, she was overtaken by a craving for the lush rampion (Campanula rapunculus) plants growing so enticingly in the witch’s garden next door. The witch caught her picking the plant and, as punishment, demanded her first-born baby, so Rapunzel was handed over after her birth.” http://rustikmagazine.com/five-historic-vegetables-elizabethan/

Rampion is also the name given to some species of the Phyteuma genus, for example, spiked rampion (P. spicatum). All parts are edible. P. pinnata (from Greek, “rock lettuce”) is endemic to the rocky cliffs and crevices of Crete; it is traditionally used in salads.

The roots of lance asiabell (C. lanceolata) are eaten in Korea both fresh in salads, pickled, and cooked via pan-frying or grilling. Referred to as doraji in Korea, Platycodon grandifloras is a common namul vegetable and one of the most frequent ingredients in bibimbap. The root is also used to make desserts, syrup (e.g., balloon flower root honey), tea, infused liquor.

For those with an interest in evolution and how plants change or are related to each other, Island Life remains an interesting and somewhat timeless book that is worth checking out if nothing for its beautiful botanical illustrations and fascinating evolutionary descriptions.