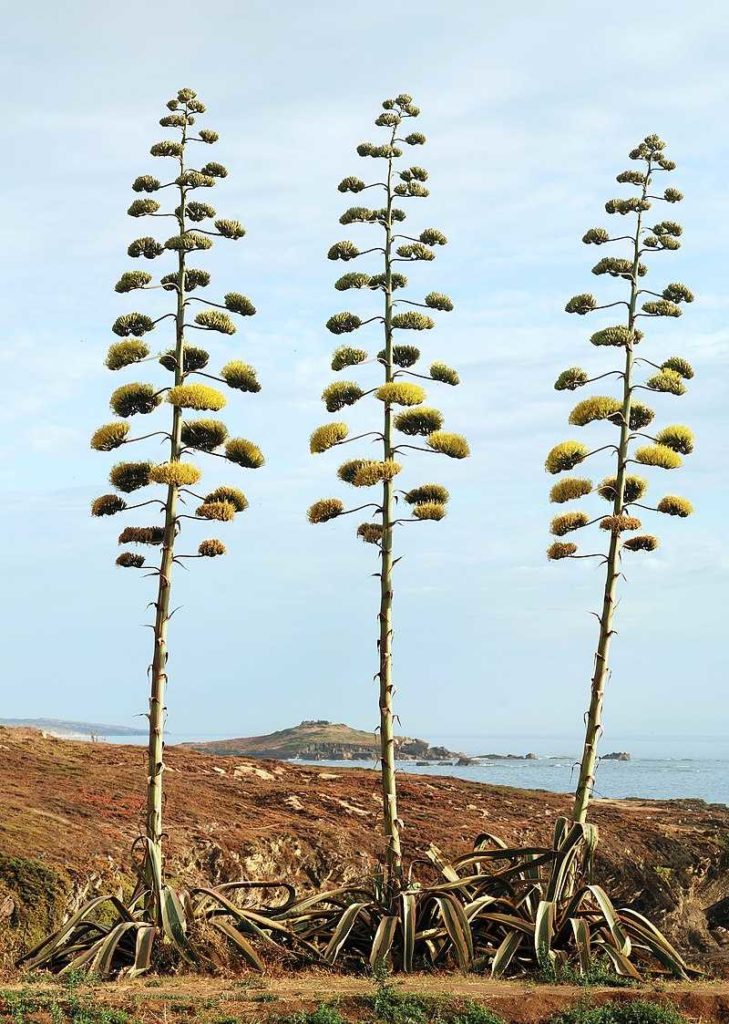

My life changed during a visit to Malta in 2016. While driving along the scenic coast on a gorgeous sunny day, a gigantic asparagus loomed in the distance. Driving closer, the 30-foot-tall behemoth emerged from a what appeared to be an aloe plant. At the time, I thought—well, I guess they have gigantic asparagus-aloe plants here, what do I know? Only later did I learn that I had seen a flowering agave plant, a botanical relative of asparagus.

Why did this change my life? This experience transformed my casual interest in plants into the plant family project you see on my website today. I was struck by how seemingly disparate plants are connected and patterns of life manifest in surprising ways.

The asparagus family in particular exemplifies this: Not only does it include asparagus and agave but also a big chunk of my (maybe your?) houseplants. The lucky bamboo they sell in stores? Not bamboo—asparagus family! Many of our favorite garden and woodland plants, like hostas, are in this family too.

Asparagus

Ah, asparagus: the plant that started it all. Asparagus ignited my interest in foraging, not necessarily by choice. For years my mom was obsessed—no, possessed—by an unending hunger to find wild asparagus. We tried many years, driving to random highway roads where she swore she saw it 5 years ago while flying by at 50 miles per hour. Let’s just say that foraging is for the patient-hearted.

Then, one day during a casual bike ride on the Oak Leaf Trail, I spotted an asparagus out of the corner of my eye. Just growing right out of the ground like in a whimsical fairy tale. The primal hunger within was fed a taste. I was excited.

It was time to go on the hunt. Where there’s one, there’s many, right? Wrong. Turns out, it’s hard to spot these tiny green things camouflaged by endless other green things. They don’t just grow in a patch all together like it’s a farm. We developed asparagus vision. At the end of 1 hour of greedy searching, we scored enough asparagus for …. One serving.

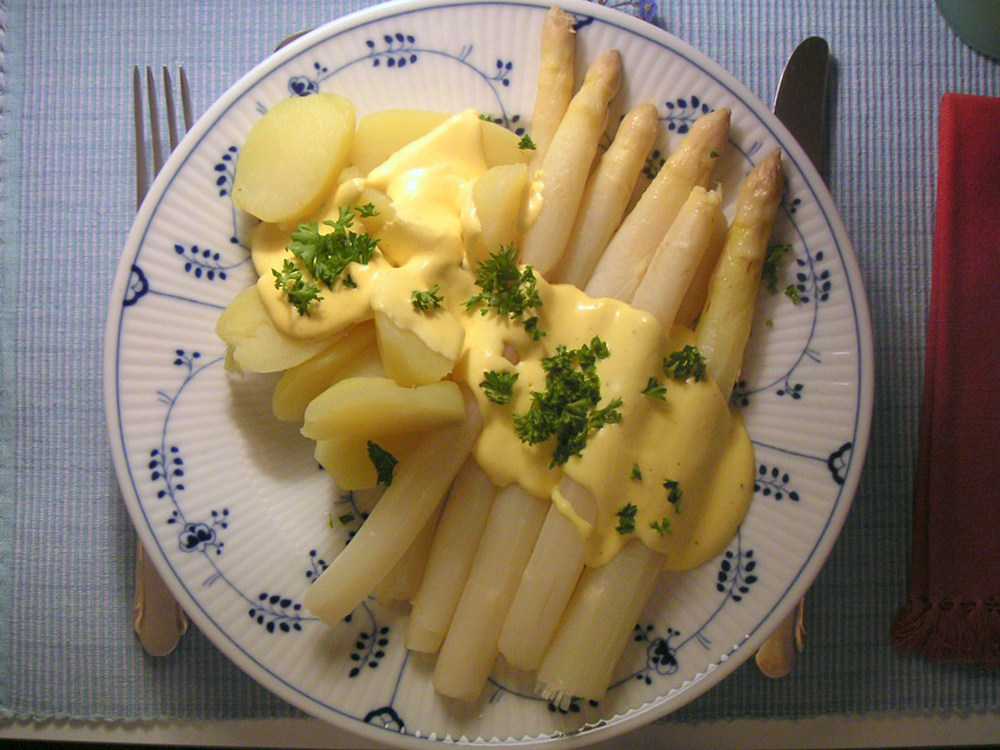

We’re not the only ones possessed by this fleeting green vegetable: asparagus festivals abound in California and Oceana County, MI (the “asparagus capital of the world”). Germany really gets into the spirit with the Spargelfest, celebrating the white asparagus harvest, the Schwetzingen festival, wherein an asparagus queen is crowned, and the Nuremberg festival, where fellow possessed souls compete in an asparagus peeling quickness contest.

What did we do with our one serving of asparagus? There are many possibilities: Asparagus can be pickled, grilled, made into soup, eaten raw in salads, stir fried, and much more.

What’s more, there are over 300 other asparagus species, some of which also have edible young shoots like garden asparagus. The Southern African scrub is home to many spindly, creeping, prickly asparagus species.

Agave: The Peoples’ Plant

What I was seeing in Malta was in fact an agave plant, also called century plants because they grow very slowly and take decades to flower. I was thus fortunate to witness a rare flowering event in such a beautiful location to boot.

The agave is a fundamental plant in Mesoamerican cultures. The flowers, leaves, rosettes, and sap are edible. In fact, the huge flowering stalk can produce several pounds of edible flowers. The spines are so strong that people have used them as sewing needles.

Agave was a major food source of indigenous people in the Southwest U.S. Archaeologists have estimated that the Hohokam people in present-day Arizona cultivated enough agave to provide 20% of their daily caloric needs.

Agave is also the source of mezcal and tequila, which are made from baking the plant hearts (piñas) and then roasting and crushing these to release the aquamiel (literally “honey water”). This liquid is then fermented and distilled.

Agave is easily confused with yucca, also in this plant family. Yucca are known for their spiky, tough sword-shaped leaves for which they are referred to as dagger plants or Spanish bayonet. Like agave, yucca has many edible plants parts and its fiber is harvested to make sandals, baskets, rope, and more. The flower petals are commonly eaten in central America after being blanched and combined with other items like sauce, tomato, onion, or chili.

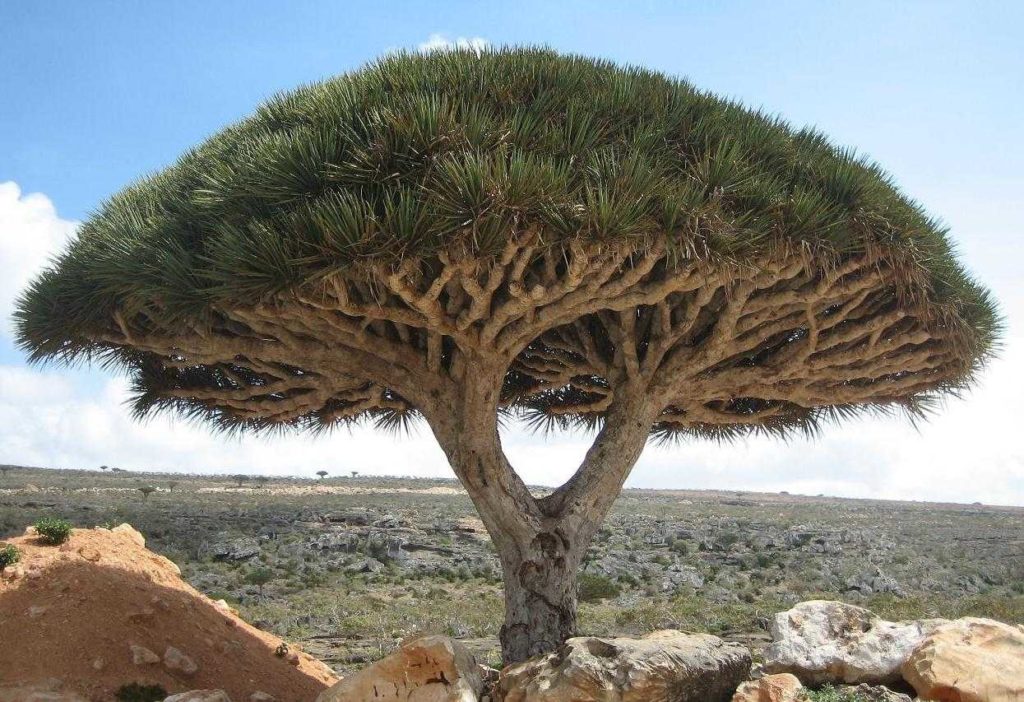

Some yucca species are more treelike, such as the Joshua tree yucca or palm tree yucca (Yucca brevifolia). They live for hundreds of years, sometimes even a thousand years. The story behind the name “Joshua tree” is commonly thought to be religious: The tree (and others with the same name as well as the namesake Joshue Tree National Park) was thought to guide Mormon settles who were crossing the Mojave Desert in the middle of the 19th century.

Dasylirion, often referred to as sotol or desert spoon, are drought-tolerant plants native to northern Mexico that look very similar to yucca or agave. Some indigenous people use the plant in ways similar to agave, such as turning the young flowering stalk into alcohol called sotol, baking the crowns and pounding into flour for bread, or using the leaves to make basketry.

Starchy Roots

This plant family contains important sources of starch. One important example is the camas plant, the bulbs of which were an important food source for both indigenous people and settlers along the Pacific Northwest, including the Lewis & Clark expedition.

Indigenous people cultivated blue camas (Camassia quamash) through controlled burns, weeding, and propagating bulbs. Cama plots were stewarded by family groups. Those who didn’t grow them traded for them as part of an extensive cama trade network. They were produced in large volumes for potlach occasions, which served important economic and social functions. Pit-roasted cama bulbs taste similar to but sweeter than sweet potato.

As prairies diminished due to livestock, the extensive cama population declined, though there are still plenty of cama prairies and marshes in the western U.S. Their mark on history is indicated by the naming of the city of Camas in Washington and many other western U.S. landmarks.

The Maori of New Zealand have had many uses for plants in this family as well. Cabbage tree (Cordyline australis) is a source of food, fiber, and medicine and has significant spiritual meaning as well. In addition to cooking the rhizomes in earth ovens to extract sugar, growing tips or leaf hearts were eaten raw or cooked as a vegetable.

Getting Clean

Some of the same species that are used as starchy foods are also used for their lathering properties Like the soapberry family, they contain saponins that produce a soapy lather when mixed with water. What’s more, some particularly fibrous plants produce soap with built-in brushes.

For example, the leaves of the octopus agave in Mexico are dried and beaten to make a soapy brush. The bulbs of the California soap plant (C. pomeridianum) are covered in fibers that can be made into small brushes. Although the saponins make the bulbs poisonous raw, they are edible after being roasted. The Donner Party purportedly were given some of these bulbs by locals.

Butcher’s broom (Ruscus spp.) is another plant with soapy qualities as well as another cleaning use: its flat prickly branches were originally harvested to make hand brooms for cleaning off butcher blocks.

Houseplants

As I delved deeper into this family, I realized that I was surrounded by its members in the form of my houseplants: asparagus fern, snake plant, spider plant, dracaenas, cast iron plant, lucky bamboo. That’s right — not even the lucky bamboo escapes the clutches of the Asparagus.

Cast-iron plant is a famously indestructible plant tolerant of neglect and cold. It became a symbol of the middle class in Victorian Britain, such as is represented by the main character in George Orwell’s book “Keep the Aspidistra Flying.”

Dracaena is another collection of plants that find their way into people’s homes. The genus name Dracaena derives from Greek for “female dragon.” Most of them hail from Africa.

Pregnant Onions

One fun section of this family is its collection of bulbous onion-like plants called pregnant onions.

Africa is home to other deciduous bulbs. Most well-known is the sea squill (Drimia maritima) which has been used both as a poison and in medicinal applications since antiquity in ancient Egypt and Greece, such as hanging outside of doors for protection against evil spirits and to ring in the new year.

Spring Woodland Flowers

This plant family checks off a lot of boxes for me: food, other human uses, houseplants, gigantic spiky leaves, weird oddities, and—just to put the cherry on top—cute little spring flowers that bring happiness after a long winter. Thus, we end this journey with pretty pictures of the spring flowers.

The common bluebell (H. non-scripta) is a popular garden ornamental plant, especially in the United Kingdom where it is a protected plant. In the wild, it grows in old-growth forests called bluebell woods.

This family even includes the hosta, a favorite hardy garden plant of many—not me, however. I have a weird unexplained disdain for them. There are possibly as many cultivars as there are hosta enthusiasts, some of whom are surely subscribing members of the American Hosta Society. There are also some very interesting “recipes” out there for these edible plants. They are grown as vegetables in some parts of Asia. I’ll pass.

Carpets of squills are a common sight in Wisconsin in spring but are actually considered invasive. Learn more about ephemeral spring flowers.

Is it spring yet? Is it asparagus season yet? I patiently wait.